In this article, we explain the terms, dig into the data and connect implications with opportunity.

By Grace Perry

Wasted food is a global challenge the afflicts low-income and high-income countries across the world and has dire environmental, economic and social consequences. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (UN FAO) estimates that approximately 30% of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted each year, which is the equivalent of 1.3 billion tonnes of food (FAO, 2014). The FAO further estimates that globally, wasted food accounts for USD 1 trillion in economic costs, USD 700 billion in environmental costs and USD 900 billion in social costs (FAO, 2014). With global warming projected to hinder agricultural outputs and population rise demanding greater quantities of food, the consequences are only expected to worsen (Gunders et al., 2017).

Food is wasted in such massive quantities largely due to food supply chain inefficiencies. The food supply chain consists of complex activities and transactions between actors that transport food from farm to fork. In the supply chain, food begins at the production stage, moves to the distribution stage, to the processing stage, to the marketing stake, to the grocery retail stage, to the food service (restaurant) stage, into consumers’ homes, to the food donation and redistribution stages and finally to the food waste management stage. There are food losses at each stage throughout the supply chain, and wasted food is commonly described in terms of where it is wasted in the supply chain.

Understanding the terms Food Loss and Food Waste

Food loss occurs before food reaches the consumer and is caused by inefficiencies in the beginning stages of the food supply chain such as harsh weather, pests and diseases, poor infrastructure, storage malfunctions, lack of technology, capacity of supply chain actors and lack of market access (FAO, 2014; Bloom, 2010). Food waste is a subset of food loss and refers to safe and nutritious food that is discarded toward the end of the supply chain because of some choice made from farm to fork, whether it be the result of an individual’s choice, a business mistake, or a government policy (FAO, 2014; Bloom 2010). Researchers have found that wasted food is not distributed equally throughout the supply chain, and that a country’s net worth is a determinant of food loss and food waste amounts. For example, in medium- and high-income countries, food waste at the consumption and retail stages constitutes the majority of food losses (Stevenson and Khan, 2013). Comparatively, the majority of food is lost during the early and middle states of the food supply chain due to the financial and structural limitations in low-income countries (Ibid). These differences between industrialized and developing countries are important when considering how to mitigate the extreme impacts of food waste in the United States.

Digging into the Data

A recent report from the Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC) finds that a total of 40 percent of food goes uneaten in the United States. That 40 percent includes the $218 billion a year, or 1.3 percent of GDP, lost to food that is wasted throughout the food supply chain and food fit for human consumption that ends up being composted, converted into animal feed, or discarded in other ways (ReFed, 2016). At the individual level, the amount of food lost costs an American household of 2.4 persons $936 per year or $2.56 per day (Buzby, J. & Hyman, J., 2012). Food loss can also be measured through dietary intake, which amounts to over 1,250 calories lost per day per person. That is half of the recommended daily intake for adults, and more than 400 pounds of food per person annually (Gunders et al., 2012). If these figures are not staggering enough, the environmental and social impacts of food waste are antithetical to the very purpose of an industrialized, global food system.

If food waste were a country, it would rank as the third top emitter of greenhouse gas emissions after the United States and China (FAO, 2013). Domestic figures substantiate the extent of environmental costs. The NRDC finds that 19% of all cropland in the United States is wasted along with 18% of all farming fertilizer and 21% of agricultural water usage. Food waste is the number one contributor to landfills today and account for 21% of U.S. landfill content and 2.6% of annual greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, food waste accounts for more than one quarter of the total freshwater consumption and 300 million barrels of oil per year (Hall et al., 2009).

As food and resources are wasted in catastrophic volumes, the global population suffers similarly from food insecurity and malnutrition rates. In the United States, one in seven Americans, or 40 million people, are food insecure without reliable access to sufficient, affordable and nutritious food. Because food insecurity is often a question of access, related to purchasing power, food prices and distribution, rather than supply, the FAO estimates that by capturing the excess food waste in the supply chain, one fourth of the food wasted each year could feed the entire world’s hungry population (FAO).

Reactions and Responses

With warning signs mounting, U.S. entities have responded to this issue over the past decade. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a national goal to cut food was by 50% by 2030. Congress has similarly acknowledged the prevalence of food waste by improving food donation tax incentives and extending them to businesses of all sizes, and introduced the first-ever explicit food waste bill in 2015, the Food Recovery Act. While the federal bill was never passed into law, its presence indicates progress, and prompted many states to pass similar legislation at the local level. U.S. businesses have also demonstrated promising action by forming consortiums, associations and alliances set to decrease food waste across the food industry. Further, media publications have reported widely on the impacts of wasted food, resulting in a rise in consumer consciousness. Educational campaigns to reduce food at the consumer level have also given rise to a notable awareness. In a 2015 consumer survey, 42% of respondents reported having heard or seen something on waste food in the past year (Gunders et al., 2017). A perplexing challenge still remains for stakeholders: how to translate the improved awareness to long-term change throughout the food supply chain.

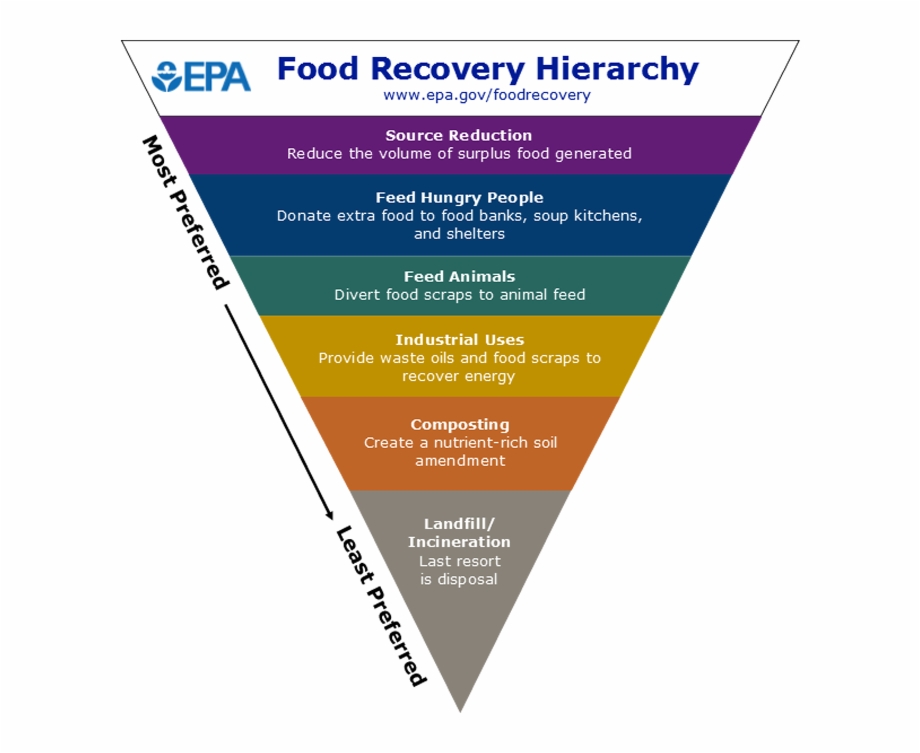

Mirroring the complexity and diversity of actors along the food supply chain, there are a myriad of solutions that seek to achieve long-term change. The Food Recovery Hierarchy (pictured above), a tool created by the EPA, is one solution that helps organizations prioritize actions to prevent and divert food waste. According to the hierarchy, the top levels are the best ways to prevent and divert food waste because they result in the most environmental, social and economic benefits. From top to bottom, the Food Recovery Hierarchy priorities source reduction, feeding hungry people, feeding animals, industrial uses like producing fuel, composting and finally, landfill/incineration. Many organizations use the Food Recovery Hierarchy to inform their food waste reduction practices, while others use it to create solutions targeted toward specific steps in the hierarchy. For example, companies that redistribute food surplus from restaurants to individuals in need are cropping up in urban areas. Technological solutions are helping producers and retailers track and monitor the quality of their food, which helps producers plan for yields and retailers plan more efficiently.

Effective regulation, consumer awareness campaigns, collaboration among stakeholders and technological innovations implemented across the food supply chain are all part of the solution to combat food waste. At The VINE, we work in the innovation sector because we believe it is a powerful place to ideate sustainable food waste solutions. We focus our resources on developing innovation, and connect resources around the region that food waste innovators can leverage, including incubators, research labs, field testing facilities, mentors and industry experts, and enable innovators to identify and accelerate their innovations. This forthcoming series of articles on food waste introduce the landscape of food waste solutions and identify opportunities for innovation and innovators to affect change. The series aims to connect food waste issues and solution possibilities with innovators who care about launching new products, services and business to help solve this problem. We hope that by establishing connections and convening the right people, we can succeed in this challenge.

About the Author: Grace Perry is a graduate student in Community Development at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on food system governance and community engagement with food systems change. Grace has a background in marketing and agriculture, and finds the intersections of agriculture, climate change and food justice especially interesting.

References

Bloom, J. (2010). American wasteland: How America throws away nearly half of its food (and what we can do about it). Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Buzby, J. C., & Hyman, J. (2012). Total and per capita value of food loss in the United States. Food Policy, 37(5), 561-570.

Gunders et al. (2017). “Wasted: How America is Losing up to 40 Percent of its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill [PDF File].” Natural Resources Defense Council. Retreived from https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-2017-report.pdf.

Gunders et al. (2012). “Wasted: How America is Losing up to 40 Percent of its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill [PDF File].” Natural Resources Defense Council. Retreived from https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-food-IP.pdf.

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., Van Otterdijk, R., & Meybeck, A. (2011). Global food losses and food waste [PDF File] (pp. 1-38). Rome: FAO. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf.

Hall, K. D., Guo, J., Dore, M., & Chow, C. C. (2009). The progressive increase of food waste in America and its environmental impact. PloS one, 4(11), e7940.

Rethink Food Waste through Economics and Data (ReFED) (2016). “A Roadmap to Reduce US Food Waste by 20 Percent [PDF File]”. Retrieved from https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf.

Stevenson, M., & Khan, S [PDF File]. (2013). Food Waste & Food Loss. Retrieved from http://app.reviewr.com/resources/dyn/files/1135881ze229f54c/_fn/Client+Insight+Deck+Attachment+-+Food+Waste+and+Loss.pdf.

FAO (2013). “Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources [PDF File].” Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf.

FAO (2014). “Food Wastage Footprint: Full-cost Accounting [PDF File].” Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3991e.pdf